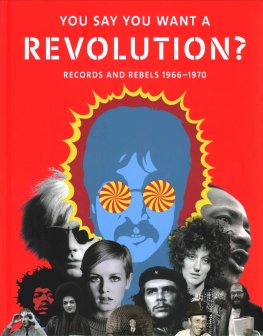

You Say You Want A Revolution?

- Records and Rebels 1966 - 1970

Editors, Victoria Broakes and Geoffrey Marsh (2016), V&A Publishing, London.

320 pages, £35.00. ISBN: 978 1 85117 8911

The book,

of which I bought the lavish hardback version, is a

souvenir accompaniment to an exhibition of the same

name, which was staged at the Victoria and Albert

(V&A) Museum from 10 September 2016 to 26

February 2017. We visited it on Monday 10

October. The V&A's advertising blurb

stated, 'This major exhibition will explore the

era-defining significance and impact of the late

1960s, expressed through some of the greatest music

and performances of the 20th century alongside

fashion, film, design and political activism.

The exhibition considers how the finished and

unfinished revolutions of the time changed the way

we live today and think about the future.'

How can anyone grasp the driving forces that brought about this era of unparalleled change? According to Jon Savage, the music journalist and author of chapter 4, there were six transformational agents in the culture of the 1960s. They were, 1] LSD and other drugs; 2] mass media; 3] the Vietnam War; 4] commerce and demographics; 5] the fear of nuclear destruction and 6] the civil rights movement. Other factors, such as fashion and music and travel, arguably deserve inclusion, but these six drivers inevitably crop up repeatedly in various guises throughout the 320 pages. The book is topped-and-tailed with introductory and concluding bits and pieces, but its main body consists of nine chapters, written by nine different authors - they vary in length, insight and, of course, personal interest. I shall take and comment on them in order, in a somewhat sentimental way.

1] A Tale of Two

Cities -

London, San Francisco and the Transatlantic Bridge.

I thought this was the most creative chapter of the

book. London and San Francisco were two of

the key centres of the 1960's revolution in music,

culture, politics, communication and just

living. I was privileged to know something of

both places. The chapter consists of 100

parallel diary entries, fictional but based on

historical events, written by two journalists based in

the two cities and connected by the so-called

Transatlantic Bridge. The latter was built

especially by the growth of air travel with New York

as the midway point. Chairman Mao's Little

Red Book, the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely

Heart's Club Band, England's World Cup victory,

Martin Luther King's assassination, the Abortion Act,

Concorde's test flight, the Woodstock Festival,

Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch, the moon

landing, the Kent State University shootings - don't

tell me these years were lacklustre and

inconsequential and not just for those two cities -

they had a global resonance.

2] Revolution Now - The Traumas and Legacies of US Politics in the Late 1960s. Nothing dominated US society during these years like the Vietnam War. When in 1965, President Lyndon B Johnston upped the US involvement from 23,300 to 184,000 troops it triggered a greater anti-war dissent, student riots and the burning of draft cards. Undergirding this was the civil rights movement with Black Power, protest marches and the burning of northern city ghettoes. I was in Harrisburg, PA one weekend when some Vietnam-returning soldiers were beaten up and when some black people were shot as they waited in their car at traffic lights. It was a dreadful double whammy that powerfully spoke the story. And add to that the ructions caused by the nascent environmental movement plus the radical feminist and gay rights' movements and you begin to understand something of Sixties America on fire. The modest tinder for these latter conflagrations can be traced to Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962), Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963) and the 1969 stand-off between police and homosexuals at the Stonewall Inn, New York. The counter-culture, both peaceful and bloody, had been launched.

3] The Counter-Culture. Much of the counter-culture was synonymous with the so-called 'underground'. This was a coalition of anti-establishment, anti-war, rock-and-roll fans who were into drugs, music and politics. They reacted against the suburban, white, conformist, middle-class. Among their heroes were Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, J D Salinger, Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Sex, drugs and rock-and-roll were their trophies. A previously-unknown youth culture was emerging and full employment meant it had money and so fashion boomed. It could be 'hippy' with headbands, embroidered jeans and flowers, or it could be 'sharp' with tailored suits and smart attire from Carnaby Street. Whereas such clothing denoted different tribal allegiances, drugs, music and dancing stirred their common pot.

4] All Together Now? Music can be societal glue. March 1967 brought with it The Jimi Hendrix Experience and the deep, deep sound of Purple Haze. One critic described it as, 'astounding, incredibly ugly but fascinating.' Yet a musical paradox was evident because in the same month, Englebert Humperdinck's Release Me was top of the UK charts. There were mods and rockers, ballads and rock, Beatles and Stones. But pop music went decidedly druggy, especially with the LSD-fuelled psychedelic experience, in terms of both its performers and its lyrics. The former were outed by the newspapers and appeared in court while the latter were scorned by Mary Whitehouse and banned by some radio stations. Everybody knows prime examples, just think of the Beatles' February 1967 single of Penny Lane backed with Strawberry Fields. And there were music festivals - everybody knows of Woodstock with its 400,000 in August 1969 and the Isle of Wight with its 600,000 in August 1970. These colossal communal imperatives of music rapidly rose and then rapidly faded.

5] The Fillmore, the Grande and the Sunset Strip - The Evolution of a Musical Revolution. Musicians need places to play and audiences need places to hear. This chapter concentrates on three of the most important auditoriums in San Francisco, Detroit and Los Angeles - they are less well known to British watchers and hearers. But the groups who found fame and fortune at these venues read like a roll call of US-UK mega-bands and include Led Zeppelin, The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, Cream, The Byrds, Frank Zappa, The Holding Company, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Who and Pink Floyd. Though these particular sites were US-based, the music they generated soon became transatlantic, even global - and it lives on even today still influencing young musicians and still winning a new generation of fans.

6] You Say You Want a Revolution? - Looking at the Beatles. The US composer, Aaron Copeland said, 'If you want to know about the Sixties, play the music of the Beatles.' I first heard them on Radio Luxembourg, but I also saw them live, with four or five of my fourth-form chums, on Saturday 18 May 1963 at the Adelphi Cinema, Slough - top of the bill was Roy Orbison. They wore suits and ties in stark contrast to their rivals, the unkempt Rolling Stones. The Beatles' short existence belies their enduring influence - they were formed in 1960, stopped touring in 1966 and broke up in 1970. Yet they were the best-selling band in history with over 600 million records sold worldwide from Love Me Do in late 1962 to Abbey Road in 1969. This chapter charts the ever-changing concepts, philosophies, music styles, lyrics, protests, humour, clothing and artwork of their later albums, namely, Rubber Soul, Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, White Album, Abbey Road and Let It Be - I've got three of these in my little CD collection. Sgt. Pepper is probably the most significant. Kenneth Tynan, critic for The Times, called it, 'a decisive moment in the history of Western civilisation.' It was not just innovative music, it was a creative declaration from the album cover to the fragmented lyrics to the intended cultural impact - it was music to change hearts and minds. It sold 250,000 in its first week of release, it was No. 1 for 27 weeks and in the charts for a total of 148 weeks. As a Beatles' footnote, the famous Abbey Road zebra crossing album cover was snapped during a 10-minute lunch-break - what a contrast to the sophistications of the Sgt. Pepper sleeve. Love or hate the Fab Four, none can deny that their music was truly pioneering and even revolutionary.

7] British Fashion 1966-70 - 'A State of Anarchy'. Mary Quant and Twiggy, the King's Road and Chelsea Girl, Sandie Shaw and Cathy McGowan - if these names mean nothing to you, then you know nothing about the revolutionary fashion of the Swinging Sixties and its London-centricity. Some of it was tat, but some of it was beautiful, some of it was jeans and t-shirt and some of it was the mini skirt - I bought my then girlfriend a paper mini-dress! And there was also the peacock revival for men - I had a gorgeous pair of deep-red velvet flares with a red-white-blue belt and a pair of fine-looking brown leather boots. But it was more than mere clothing. It signalled the cause-and-effect that gender stereotypes were becoming plastic, the single girl was replacing motherhood, consumerism was the new religion and individualism was the new ideology. The Permissive Society was here.

8] The Chrome-Plated Marshmallow - The 1960s Consumer Revolution and Its Discontents. And so was the Consumer Society. Once upon a time we were happy with well-designed, long-lasting, utilitarian products, now we wanted things and 'stuff', much of which was 'pop' and vulgar and ephemeral. Yet it was all so desirable because novel technologies and materials could make it cheaply and readily-available for us. We were heading for the New Age of hedonistic consumerism. And in true counter-cultural fashion, the dissidents and malcontents found common cause in environmentalism and conservation and a mother-Earth, commune-living movement. And, as if from nowhere, arguably the greatest revolutionary driver of the 20th century, electronic computers, both macro and micro, materialised.

9] 'We Are As Gods ...' -Computers and America's New Communalism, 1965-75. These 1960's back-to-the-land frontiersmen of the US, with their shopping bibles, the Whole Earth Catalog, thought they were turning their backs on the industrial-consumer society, whereas they, as brilliant innovators and resolute communicators, were actually pushing towards a new and entirely different frontier - the rise of networked computing. Nor were these disaffected New Communalists alone - whereas they sought revolution through shared social action, the New Left sought it through political action. In truth, the tandem movements brought about their distinctive transformations that then coalesced to form much of our present-day 'technocracy with a consciousness'. Geography played its part too. The San Francisco peninsula was home to countless commune dwellers but it also housed the computer-age prodigies, like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, in what would become Silicon Valley. The two movements cohabited and often unwittingly created shared tools of counter-cultural change. After all, it was at the end of the Sixties that the computer mouse [organism meets machine] was invented!

And in conclusion. I found this book and its associated exhibition warm and fascinating. It was like returning to my late teenage years with a friendly guide and interpreter. I lived through those 1966 - 1970 years and they had a profound influence on my inchoate worldview, not least because I became a Christian and a university student during them. For me those personal episodes were sufficiently revolutionary. And I don't want to become anything less than revolutionary, in my own small way, in my latter years. I fear becoming laissez-faire and boring and disinterested. And as I've read of the late Sixties, in the back of my mind has been this thought - in 1972 I attended a huge jamboree of young Christians at Urbana, near Chicago. The main speaker was John Stott and the title of the conference was Christ the Liberator. Much of the hoped for and so-called liberating revolution of Sixties 'love and peace' and other wholesome aspirations have since crumbled and faded. So often the wrong roads were taken. They petered out. The real Revolution that we all needed, then and now, is a permanent encounter with the liberating and revolutionary Lord Jesus Christ. 'I am the Way and the Truth and the Life' - that is the key to understanding the bankruptcy and failures of the Sixties, and it is entirely missing from this book.